The Crichton Centre for Memory & Wellbeing - Competition

The Crichton Trust / Institutional Campus & Estate / Dumfries & Galloway

3rd Place

The Crichton’s ambition to connect people, place and the past to shape the future struck us as a beautiful and important idea at the outset of this project.

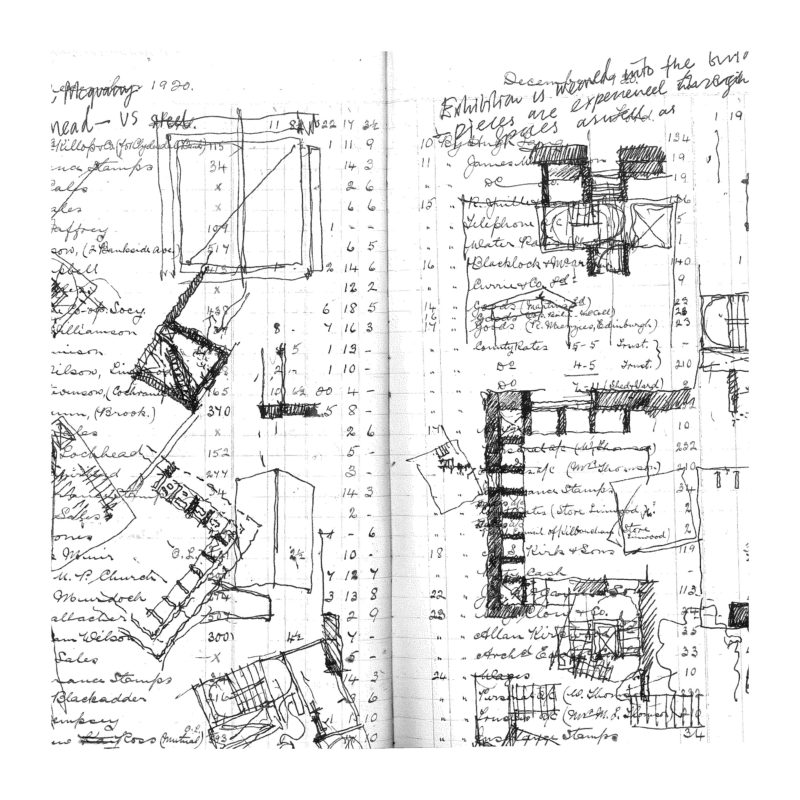

Our initial fascination with, and interrogation of, the site stemmed from its many intertwining stories of healing, geology, history and production. The layers of meaning and potential below the surface are extraordinary, and every thread we pulled throughout the competition process opened up new lines of enquiry and generated new questions.

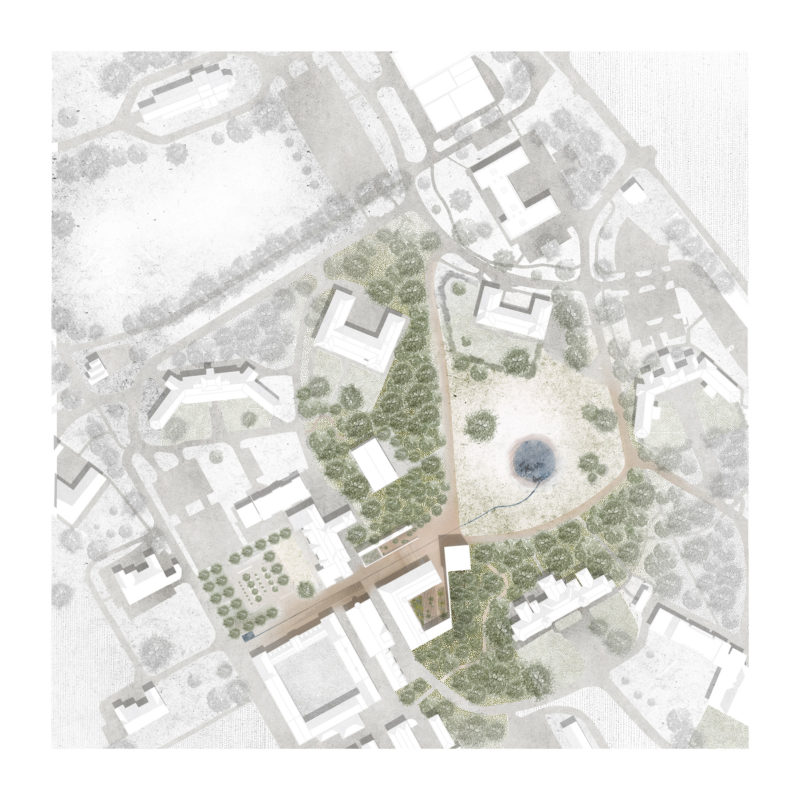

The site’s development witnessed a series of landscape ideas in succession. The initial gesture of the hospital set in an idealised pastoral landscape connecting to the river and onto Dumfries beyond is made explicit in the early views of the building. However, this site experience was progressively amended over time with the addition of the Solway cluster and 1900s ward houses, both with their own spatial logic and landscape ideas.

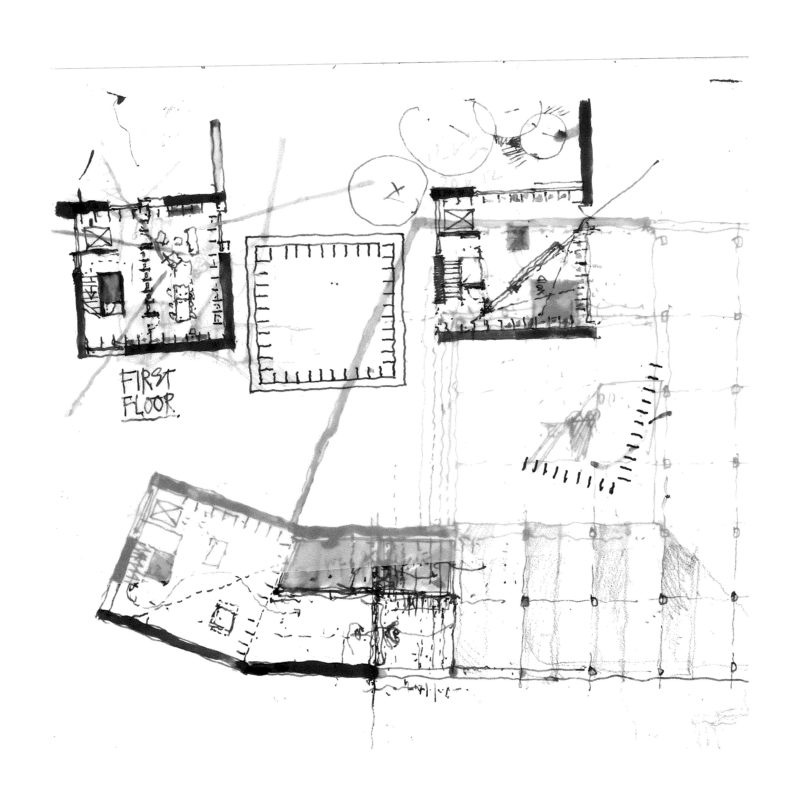

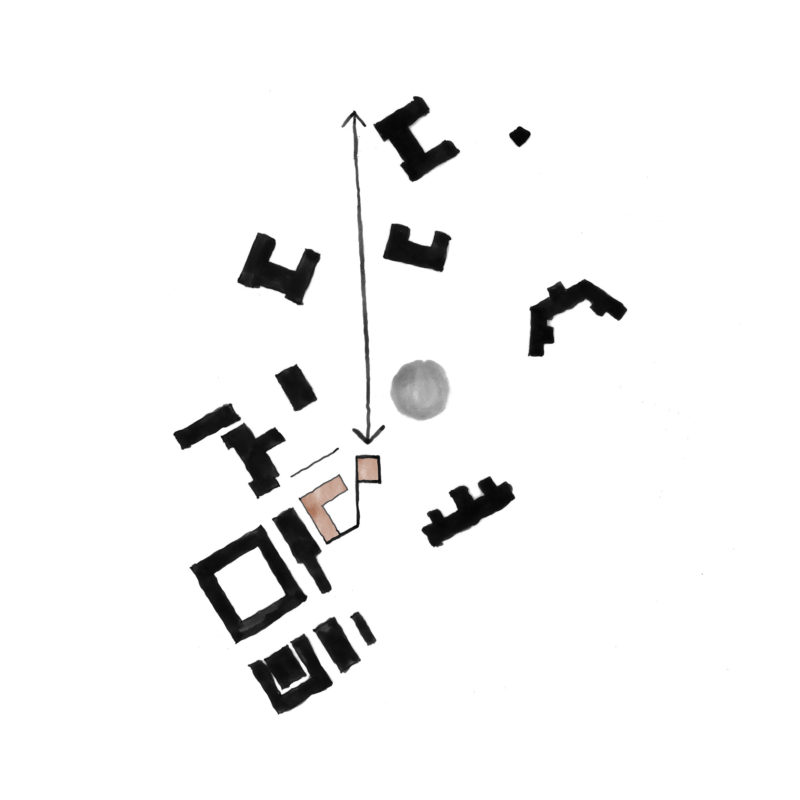

As a result, our approach was to re-imagine and clarify that landscape idea, to remake and reinforce it in the context of the new project and the contemporary and future uses of the site. We also found, around Solway, something approaching the quality of a street; of enclosure and active edges reinforced by the new cafe at Crichton Central, which is unique on the site. The idea of the street was important to us - a spatial and circulation logic, but also a social metaphor for a shared place of accidental encounter and exchange - the experiences which sustain and enrich a sense of community.

We further proposed reinforcing the open space and clarifying its edges with new woodland planting. This would become anchored by the new building and the landscape intervention of the new body of water, a relic of the quarrying process. A rill would run from this body of water down the site, echoing the rainwater which runs off the hills and into the Nith, leading users through the site and along the new ‘street’ of terraced, inhabited landscape. The street would therefore sustain a range of incidental social interactions and larger-scale events. The woodland itself would be a landscape to explore, with accessible routes through this new territory and a new wildlife habitat. Productive garden and orchard use was proposed for part of what is presently a carpark in front of Crichton Central, extending the existing green space and activating the edge of the new street.

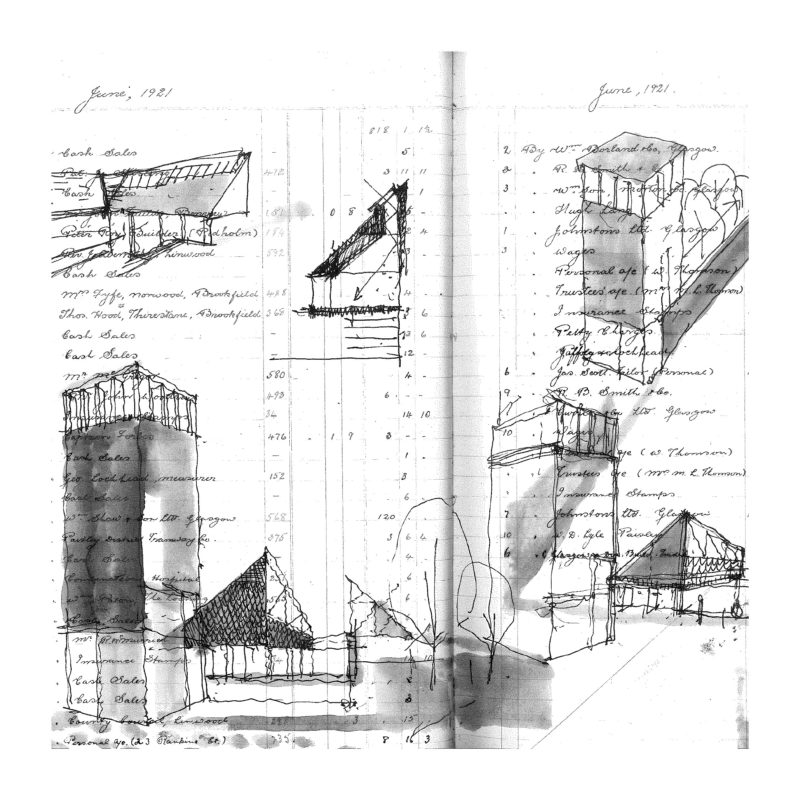

Something like a barn

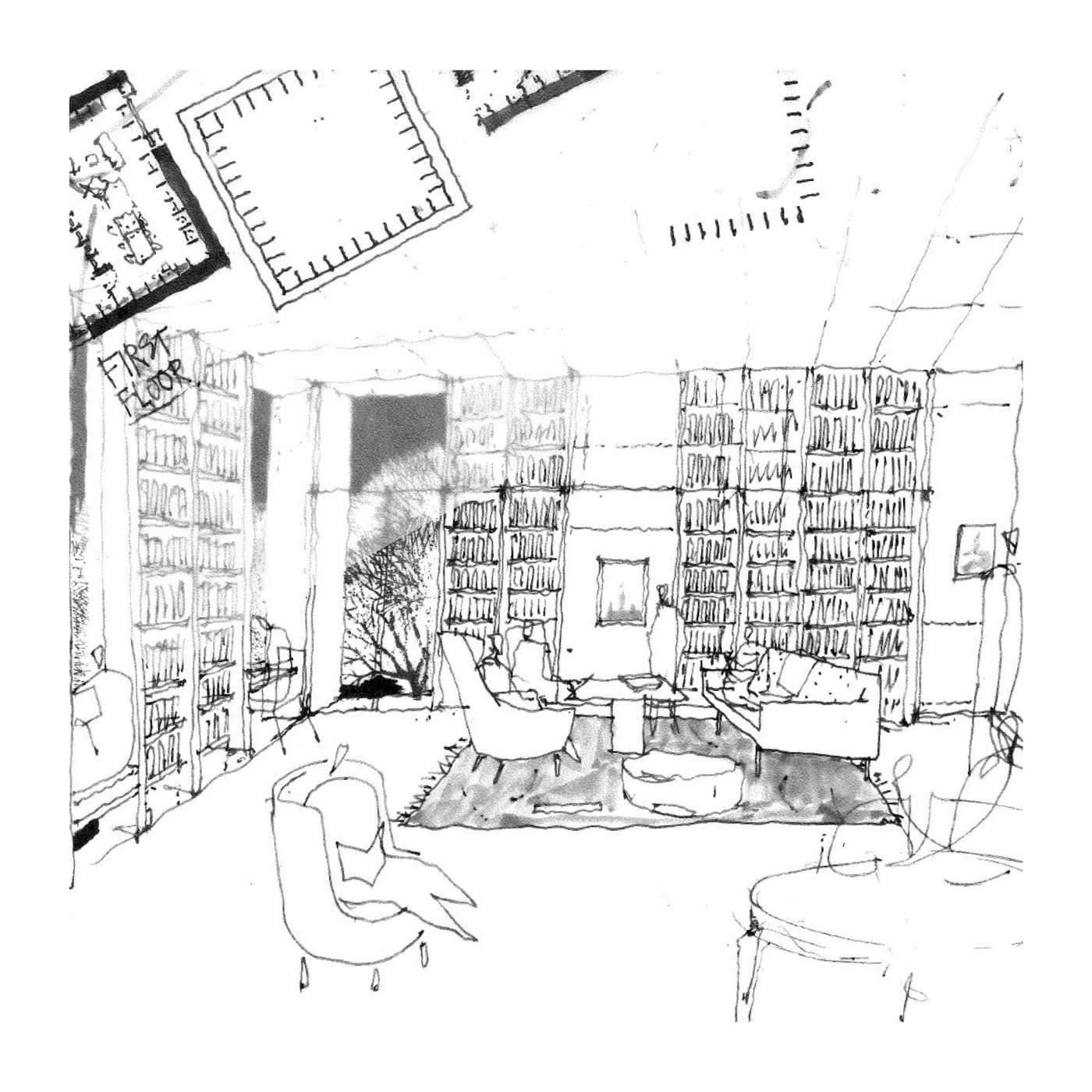

A natural affinity with the remarkable agricultural barns on the site was suggested. They are bright, airy, and connected directly to the outside. A grid of post-tensioned sandstone columns gives these buildings their identity, structure, and spatial order - using this material in a way that would be unique on the site to generate distinctive and flexible spaces. We proposed making two sides of a courtyard with a building like a barn to house these spaces, and in their section, a mezzanine or gallery allows for smaller-scale groupings than in the main spaces.

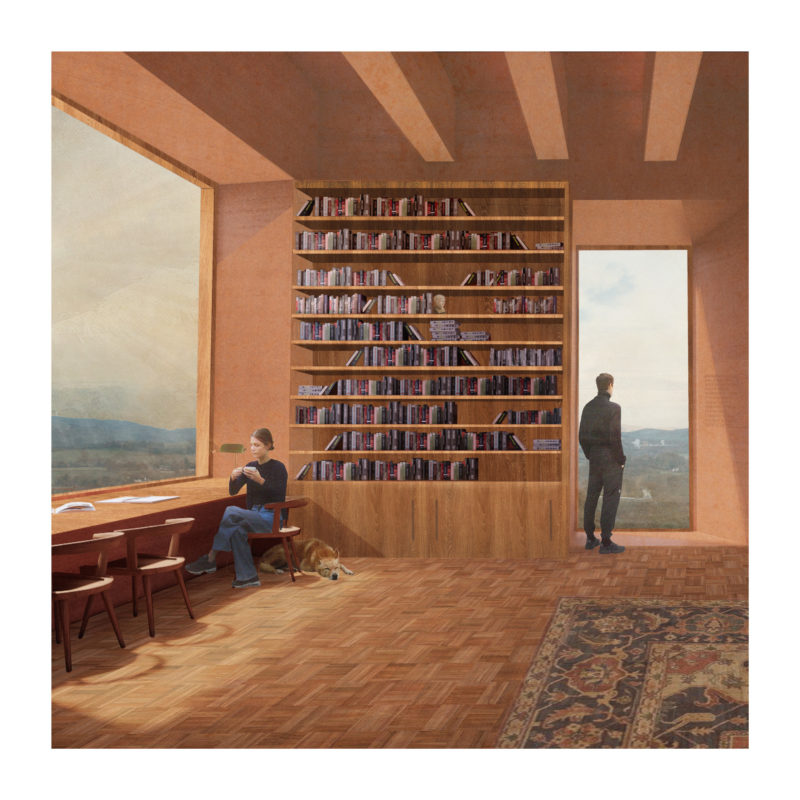

Something like a tower-house

In contrast, focused study, encounters with the archives and collections, and private reflection call for something more intimate, protected, enveloping, and perhaps quasi-domestic. The idea of the Scottish tower house - because it suggests a stack of distinctive, characterful rooms formed from a solid stone edifice - seemed very relevant. The significance of quarrying that very stone from the site felt like a powerful act.

Building with Stone

The homogeneity of the construction materials across the site is striking. In particular, the preponderance of the Dumfries sandstone is perhaps the site’s most significant material characteristic. In a climate crisis, we cannot, as architects and engineers working in the 21st century, make buildings this way now. Building structure needs to be kept warm and dry; cold bridging must be carefully controlled to minimise heat loss. This suggests to us an idea which at first seems counter-intuitive - to build from stone (rather than clad a building in a stone facade), we need an external skin that isn’t stone. Post-tensioned stone is an extraordinary innovation - this stone, in particular, is substantially more robust in compression than concrete. Post-tensioning allows the material to be used like concrete but with more slender members, shallower beam depths, less material and weight, and vastly less embodied carbon. It is beautiful and requires no further linings internally; its thermal mass stabilises temperature fluctuations, and it is of the site (it is the very bedrock on which every building is founded), making its use extremely interesting.