Vacancy - Part II graduate Architectural Assistant/Recently Qualified Architect

Hoskins Architects is looking for enthusiastic Part II architecture graduates/recently qualified architects to join us in our Glasgow studio, initially for a twelve month fixed term.

The successful applicants will work alongside project architects, associates and directors, on a wide range of projects.

Our practice is a busy and creative environment with an award winning portfolio of projects across a whole range of sectors. We’re looking for the right people to help us build on that success by joining our talented teams working on recent new project wins and our existing varied workload.

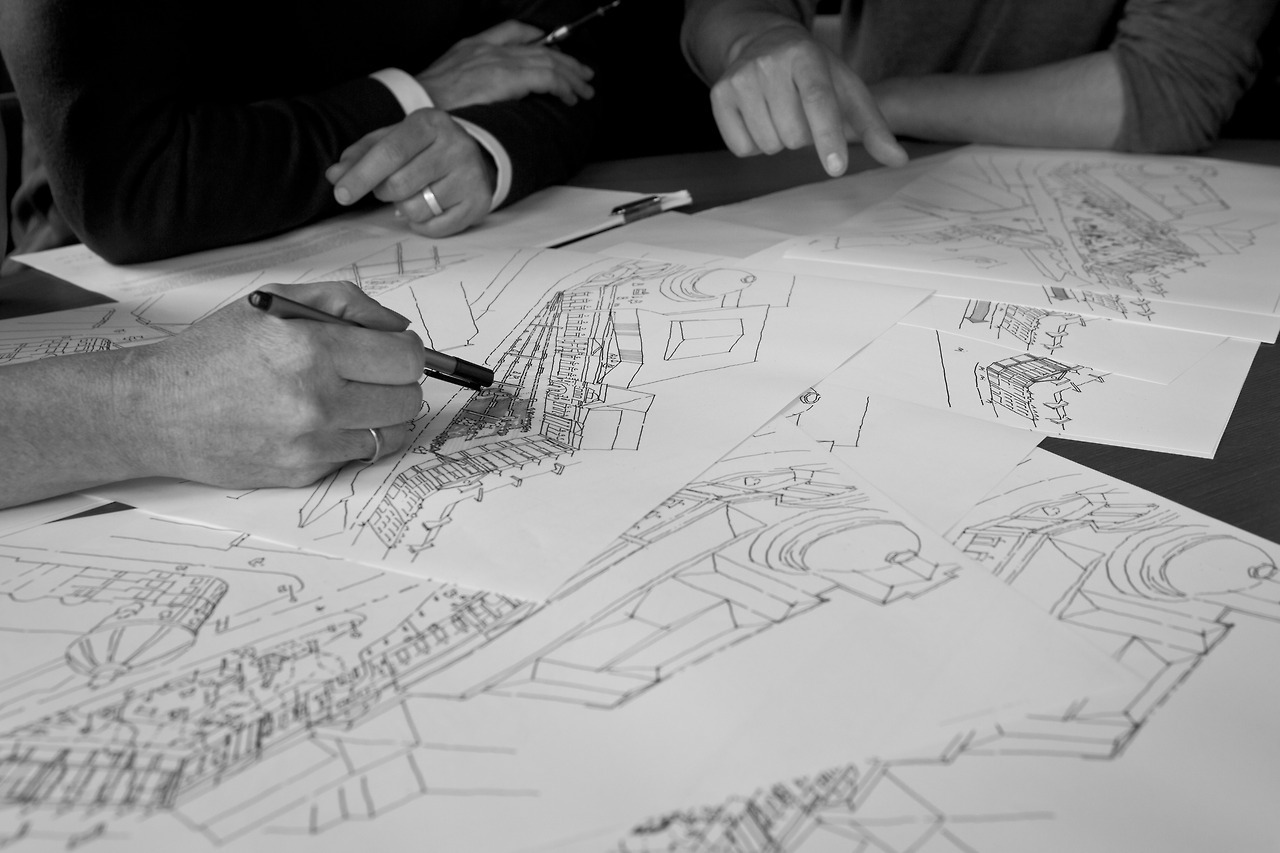

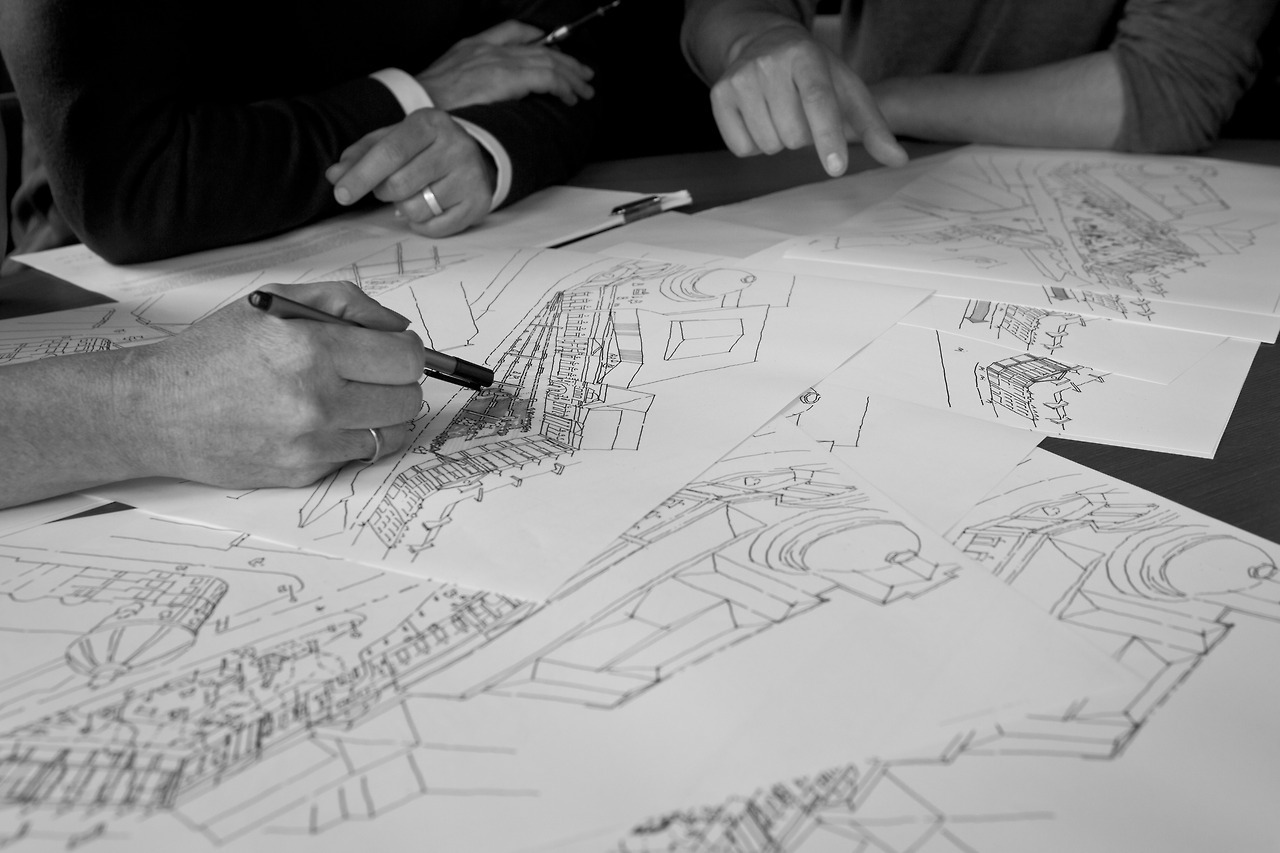

We look for people who are articulate, curious, creative and interested in design. We want good designers, good communicators and people who want to contribute. The ability to sketch beautifully and/or produce top quality visuals is a must. The office uses Vectorworks, Sketch-up and Photoshop and a knowledge of these is preferred but not essential. Experience of producing tender and construction drawing packages would be an advantage, as well as some site experience.

Our office is fast paced, friendly, focused and fun. It’s a great place to start and grow your architectural career.

Hoskins Architects is an equal opportunities employer. No agencies please.

Closing date 2 March 2018

Please email your CV and examples of work to: [email protected]

Successful applicants will be invited for interview and required to present their portfolio.

Celebrating Rockvilla’s RIBA National Award win

The National Theatre of Scotland’s new HQ, Rockvilla, was amongst 49 winning projects (one of only three from Scotland) being celebrated at the RIBA National Award Winners Party, held recently at Francis Kéré’s 2017 Serpentine Pavilion.

Director Chris Coleman-Smith and Associate Rory McCoy, the team responsible for delivering Rockvilla, journeyed to London for the event. They greatly enjoyed the chance to visit the pavilion, with its beautifully crafted wooden canopy and blue curving walls resembling something of a simplified, textile-like, patterned tree, which provided the perfect setting for the summer evening reception.

Rockvilla, adding the RIBA National Award to its already impressive haul of awards, has been described by the client as a ‘game-changing resource’ for the National Theatre of Scotland, and have greatly commended the building for transforming the way they are able to function on a day-to-day basis. Lucy Mason, the Company Director, said ‘Instead of being in tiny offices at our old base in Civic Street, or scattered around across the city, we’re now all in the same space, and able to see that we are a company. It makes all our communications so much easier and more efficient, and everyone is really loving it.’ In addition, thecclient has recognised the design team personally for their commitment to the Company’s ethos, and for their understanding and enthusiasm throughout the project.

You can learn more about the project here.

July 2017

Double win at the RIAS 2017 Awards

Celebrating the best in new Scottish architecture, both

Eastwood Health and Care Centre, and Rockvilla - the new HQ for the National

Theatre of Scotland - have won Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland

awards. We are delighted to be the only practice with two

projects among the twelve inspiring buildings given RIAS awards

this year.

This follows the news earlier in the week that Eastwood Health

& Care Centre won the design award for best building under 25,000sqm at the European Health Care Awards in London. Caroline Bamforth, East Renfrewshire Councillor and Chair of the East Renfrewshire Integrated Joint Board, said: ‘It is a fantastic state-of-the-art facility, bringing

together health and social care services under the one roof for the first time

in Eastwood. The busy community café on the ground floor also makes it a great

community hub for local people.’

These awards bring recognition to not only to those in the

project team, but also our wonderful clients. Simon Sharkey, associate director (Learn) at the National Theatre of Scotland spoke of his experience now working in their new purpose-built space: ‘The luxury of being able to walk a few yards to have a vital conversation with your colleagues cannot be underestimated. The impact of the building and how it allows us to work makes me wonder how we managed before. Seeing our students, community members and professionals all share the same space, finding out about each other’s projects and all feeling

part of the same thing is simply joyful.’

These great buildings are the result of much hard work and

belief of many individuals, and we would like to thank everyone involved for their continued support and enthusiasm throughout the process of bringing them both to very successful completion.

More about the projects can be found via the following links:

Eastwood Health and Care Centre

Rockvilla - National Theatre of Scotland HQ

June 2017

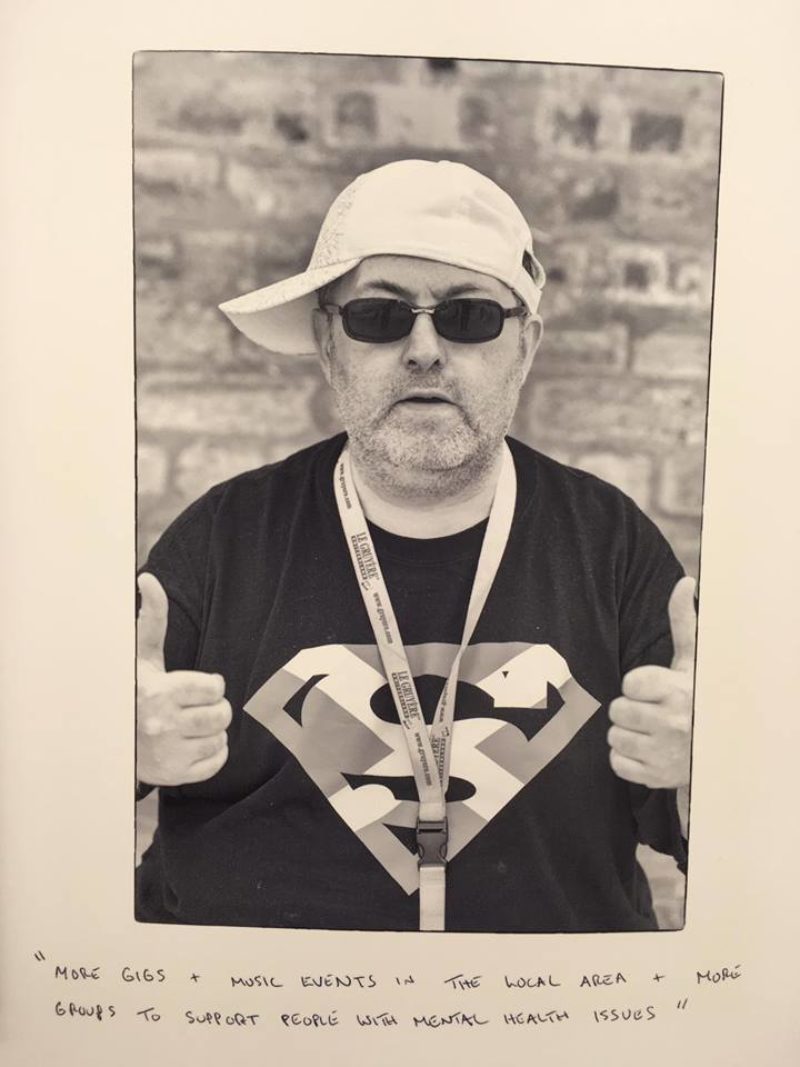

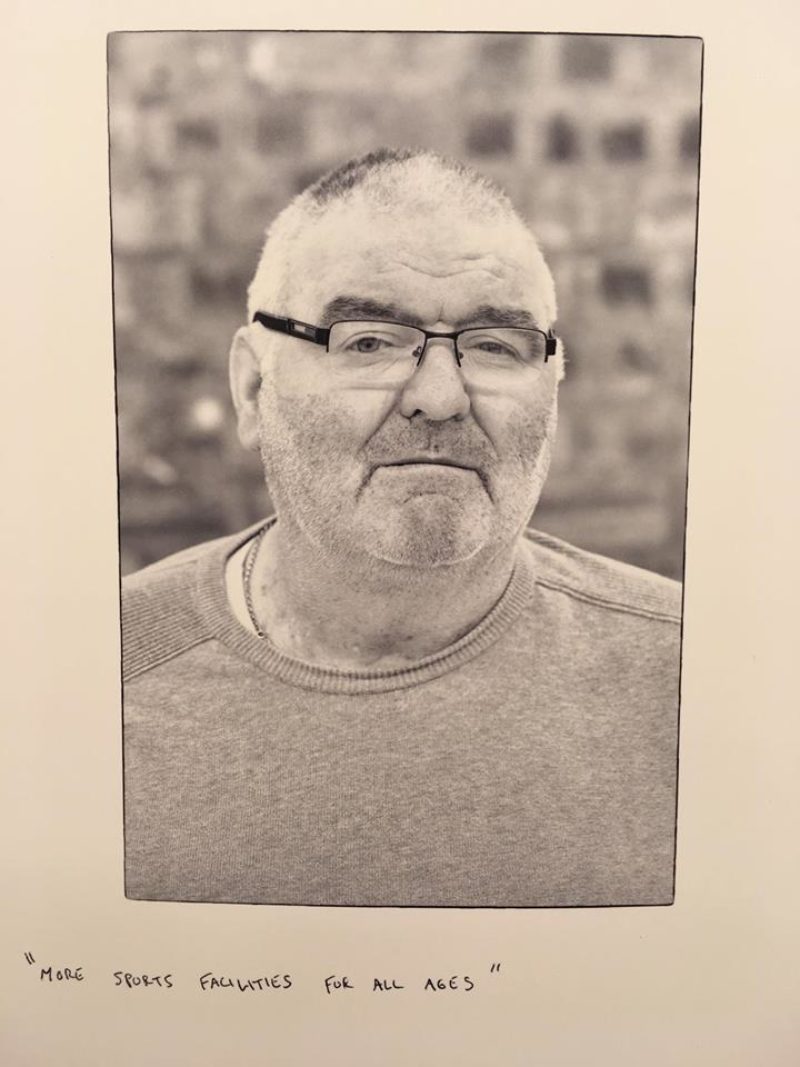

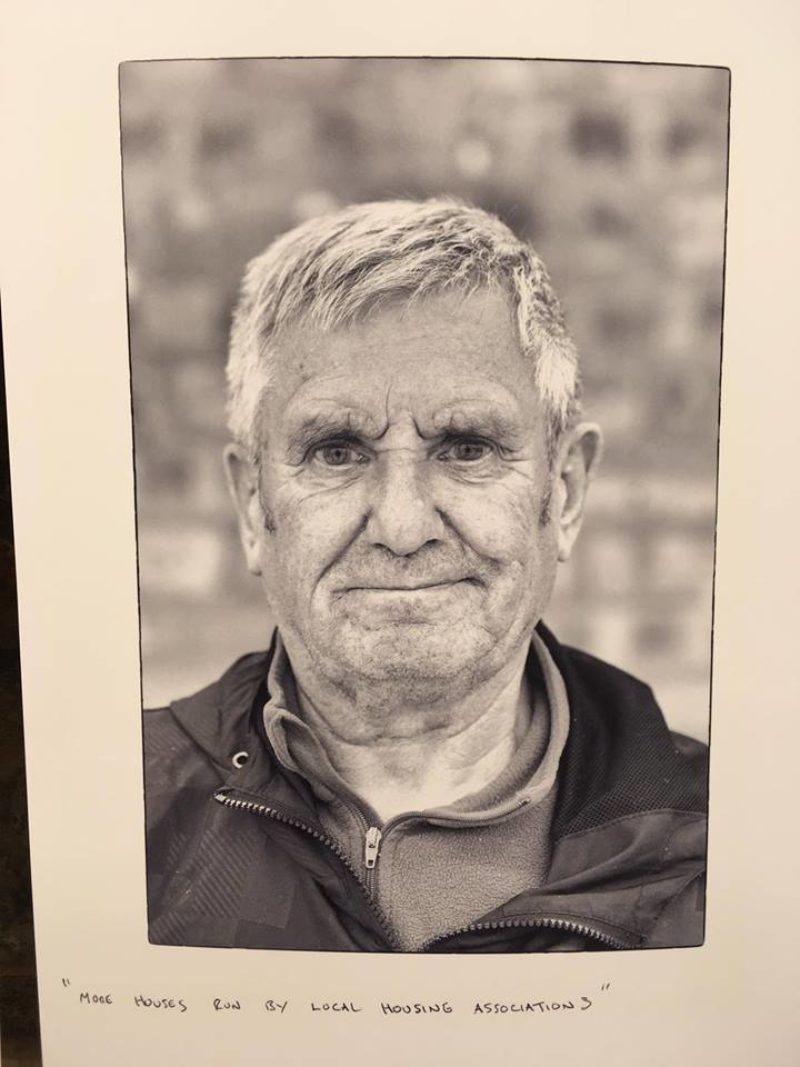

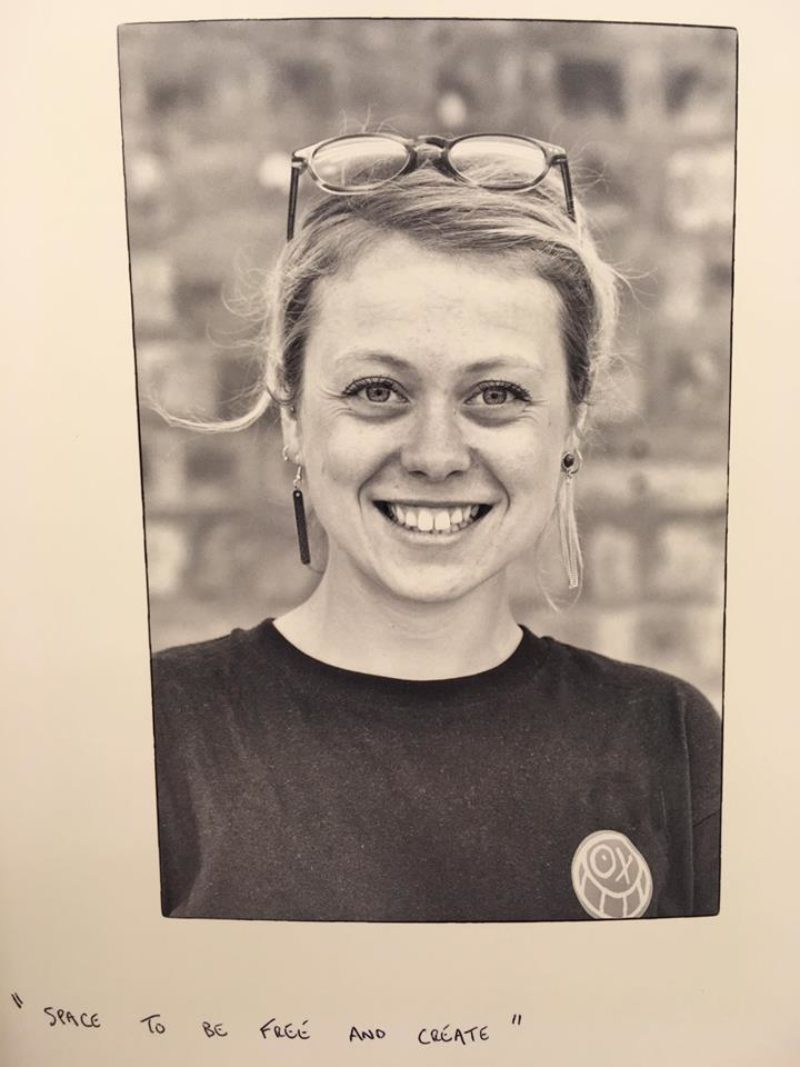

Easterhouse public charrette 13 May – 24 June

Over the next few weeks we are teaming up with Thriving Places Easterhouse and landscape architects, Erz, to run a community design programme to plan a better centre for Easterhouse.

The project seeks to identify major improvements required to both the Shandwick Centre and the surrounding facilities. The ambition is to create an overall better environment, and increase the activities available to the community – plus anything else the public think needs to happen.

From now until 12 June, the team will be in the old Savers unit in the Shandwick Centre on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays. Everyone is welcome to come in, hear more about the project, and tell us your thoughts over a cup of tea. Free events will be run, including portrait drawing, photography workshops, and pop-up music and film studios. Family and kids activities will be run on Saturdays.

Following on from this, between 21 June - 23 June, we will have a busy programme of events in the Phoenix Centre, and welcome the public to attend and give input.

Keep an eye on Thriving Places Easterhouse’s Facebook page for news and regular updates.

Portraits taken by Colin Tennant featuring some of the locals who came by to share their thoughts.

May 2017

19 May, 2017

Architectural Staff Required

Part I Architectural Assistant

Part II Graduate Architectural Assistant

Experienced PT III / Recently Qualified Architect

Hoskins Architects are looking for enthusiastic and experienced applicants to join our Glasgow studio, initially for a fixed term contract.

Successful applicants will work alongside project architects and the wider management team on a number of high profile projects.

Our practice is a busy and creative environment with an award winning portfolio of projects across a whole range of sectors. We’re looking for the right people to help us build on that success by joining our talented teams working on recent new project wins and our existing varied workload.

We look for people who are articulate, curious, creative and interested in design. We want good designers, good communicators and people who want to contribute. The ability to sketch beautifully and/or produce top quality visuals is a must. We are looking for people who enjoy working in a team and relish a challenge. The office uses Vectorworks, Sketch-up and Photoshop and a knowledge of this would be an advantage but not essential. For PT II/Architect positions experience of producing tender and construction drawing packages would be advantageous.

Our office is fast paced, friendly, focused and fun. It’s a great place to start and grow your architectural career. Salary based on industry average.

Hoskins Architects is an equal opportunities employer. No agencies please.

Closing date 8th May 2017.

Noting the position you are applying for in the email title please email your CV and examples of work to: [email protected]

Successful applicants will be invited for interview and required to present their portfolio.

Visiting Florim’s ceramic tile factory in Italy

Last year architect Kirsten Stewart was invited by Ora Ceramics to visit the Florim headquarters and factory in Modena, Italy. It was an insightful trip, rewarding her with a detailed understanding of the product and manufacturing processes. Kirsten gave a presentation on what she learnt, allowing us all to better understand the journey from dust to tile.

Background

Modena, Italy, is an area renown for tile manufacturing with some 300 different companies based there - Florim is one of the largest ceramic tile factories in this area.

They offer tiles for a variety of uses, projects and markets. The largest tile they produce is the magnum wall and floor tile, which is available in an extremely large format with sizes up to 1600 x 3200mm - huge! During our visit the Florim team demonstrated how this tile size is handled, which is similar to large sheets of glazing, with four men required to lift the tiles in to place.

Interesting facts

Having seen bicycles parked all around the factory, we were amused to discover that because the factory is so large, the team ride them to get from one side of the factory to the other.

All the water used in the factory is recycled, cleaned, and reused on site. The majority of the factory processes are carried out by machines and robots, which transport materials around the factory; except the last process – the visual inspection – which can only be done by human eye in order to check for imperfections on each tile. Those carrying out this job are only able to do so for 30 minutes at a time, before they have to switch and take a break.

The impressive vertical warehouse used for storing tiles ahead of transportation, cost 14 million euros to build, and stores 35,000 palettes at any one time – which is however, only a relatively small part of the factory.

April 2017